- Home

- Quinn Sinclair

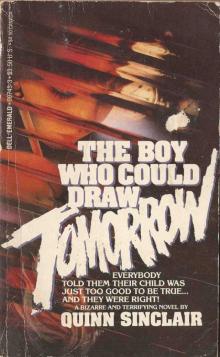

The Boy Who Could Draw Tomorrow

The Boy Who Could Draw Tomorrow Read online

She saw it now, the inking so huge through the glass it was like worms, some curving, some coiled. She moved the loup around, sliding it back and forth across the paper so that she could orient the eyes in relation to each other. The tiny circles Sam had drawn to form the pupils leaped up like thick black doughnuts, the paper at their centers like small fields of squashed white leaves.

She sat there in the roaring silence of minutes that lengthened into the howl of a stone-dead hour, again and again lowering her head to peer into the loup, again and again raising it to gape blindly at the blazing wall of tile.

Each time she bent her head to the loup, she begged God to make it change.

THE BOY WHO COULD DRAW TOMORROW

Quinn Sinclair

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or incidents is purely coincidental.

Published by Dell Publishing Co., Inc. 1 Dag Hammarskjold Plaza New York, New York 10017

Copyright © 1984 by Quinn Sinclair

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the Publisher, except where permitted by law.

Dell ® TM 681510, Dell Publishing Co., Inc.

ISBN: 0-440-00745-3

Printed in the United States of America First printing—April 1984

Not a word will he disclose, Not a word of all he knows . . .

robert louis stevenson

For A.A., INSPIRATION—NAY, BREATH

PROLOGUE

Watch him. Watch him as he does what he does. See that it is effortless, yet meticulous, and that it happens very fast.

First, he takes a pad thick with many sheets of paper, and he parts them eagerly to expose a fresh, white page. With his left hand, he now takes up the instrument he favors for the extrusion of black ink, an ordinary felt-tip pen endowed with a remarkably hard nib.

He touches the nib to the paper, a field of limitless possibility—and then the boy begins, the pen skittering from here to there in quick, electric motions as the segments of a deep design accumulate swiftly on the page. In seconds, sometimes minutes, the parts coalesce, the picture comes clear.

What is it?

It could be anything—for he is a small boy and thus a colossus in what he imagines. Perhaps he draws his mother—or the sister he does not have. He could draw Heaven if he wanted—or the worst monsters loosed from Hell. He is bound by nothing as his senses trail helplessly after the nib traveling its indelible course across a universe of paper. He is, after all, a child—and life has still to instruct him that a Pilot Razor Point pen is no more than a mere mechanical contrivance, and that a 9 X 12 All-Purpose Jumbo pad is just so many sheets of paper—things finite, things perishable, products manufactured to be sold for profit and not for the purpose of performing magic.

There! He is finished now. You would think it took no time at all. Yet centuries, whole epochs, a history beyond fathoming guided the hand that wrought the awesome inkings which yield the picture on this page.

What is it?

It could be anything—for he is no more than a boy and therefore stupendous in what he imagines. In this, be warned, the child is like a god, and the pen his terrible scepter—while the 9 x 12 pad before him is nothing less than the whole wide impending world.

CHAPTER ONE

A week after Hal Cooper was promoted to chief of publicity at Manhattan Records, his wife Peggy—a trim, brown-haired woman—was named head window-dresser at Bloomingdale's. Neither of them would have been Central Casting's idea of the roles they'd been assigned. Hal was a big, easy-going man, a fellow with more freckles than you'd try to count, whereas Peggy—Pegs to her dad back in Pensacola and Pegs to Hal—had the sort of crisp good-looks that made you think suburban matron and Junior League, a far cry from the sleek, hardbitten style common to women who worked in fashion.

Despite the hectic pace of their jobs, the Coopers were a relaxed, carefree couple, quick to smile over small pleasures, eager to pitch in and lend a hand, willing and friendly even when the pressure was on. Their boy Sam—a happy, spirited child of six—was a perfect facsimile of his parents, featuring Hal's freckles and Peggy's clean features, exuding the warm and cheerful manner that made people so fond of his mother and father.

The Coopers were special. But it wasn't the kind of specialness that aroused envy. On the contrary, it was because the Coopers appeared to be such an ordinary couple, so clean-cut and wholesome, that you kept your eye on them and watched their progress in the world. It made you feel good when things went well for Hal and Peggy. It made you feel that, in this one case at least, the time-honored virtues paid off.

It was the same with Sam.

For example, his nursery school teacher—the one he'd had last year—was always sending home little flattering notes, a few hastily written sentences whose breathless praise of Sam delighted Hal and Peggy, but whose content it was their habit to take in modest stride. It seemed that Miss Goldenson never tired of composing these little notes. Indeed, weeks after the term was over, still another one came, this time by mail.

"It has been such a joy to work with Sam! His is such a sweet disposition! How special he is, this kind, light-hearted boy of yours. And so talented at drawing pictures! Whatever you do, at all costs you must encourage his interest in art! Have a happy, healthy summer! Yours sincerely, Cecile Goldenson."

***

Of course, the Coopers were thrilled to have these endorsements of their son. As effusive as they were, in truth they were probably not far from the mark. Sam was an extraordinarily good boy. But why not? His was a happy, loving home. Yet proud as they were, Hal and Peggy were sensible people, and they did their best to keep their pride over Sam in check. After all, to get too showy about it wasn't the way the Coopers did things. It wasn't healthy to get all puffed up. The gods might get jealous, and then what?

As for Sam's being so crazy about drawing, well, Hal and Peggy weren't sure how much talent the boy really had. But they were glad he liked to do something creative. It was good for Sam to have an emotional outlet, a means of expressing his deepest feelings and secrets. Still, pleased as the Coopers were that their son loved to draw so much of the time, they cultivated no fanciful illusions about the boy's passion for paper and pen. After all, how many times had Peggy picked up a book on early childhood development and read there that lots of kids showed startlingly precocious achievement of some kind, only to have the impulse wear off when school and homework began to hit hard?

Wasn't Sam slated to start first grade in the fall? Chances were he'd forget all about drawing once school got really serious.

***

When the set of promotions had come through, the Coopers were both delighted and surprised. Hal wired his folks back in Grand Island, Nebraska, and Peggy called her dad, a retired airline pilot and widower who passed his days tinkering with humorously pointless inventions.

"Pop?" Peggy cried when her father picked up the phone in Pensacola. She was grinning impishly at Hal, who stood next to her ready to talk too, listening and beaming.

"It's Pegs, Pop. Guess what!"

She told him the good news and put on Hal and then called Sam to say good-night.

Later on that night, Hal and Peggy made love a little longer and more ferociously than usual. Even so, afterwards, as spent as they were, neither of them could drift off to sleep. They lay huddled together, dreamily musing on all their good fortune. Near dawn, when the grey light began snaking itself around the edges of the

drawn window shade, Peggy wondered aloud if with their new salaries they might start looking for a better place to live, a larger apartment in a safer neighborhood. Hal stroked her hair and agreed that it was certainly in the cards, that it was high time Sam had a real room, something big enough to handle a double-decker so that, now that he was getting old enough, he could sometimes have a friend stay overnight.

***

It was no use trying to sleep after that—they were much too excited with the idea of what the new money really meant—a decent apartment at last.

Peggy got up and went to the kitchen to make coffee and start breakfast. Hal rolled over and watched her go, appreciating with a connoisseur's detachment the strong, straight back and the voluptuous cadence of her high hips.

He reached to the floor and pulled his briefcase up onto the bed. He figured he'd use the extra hour to polish some releases he was working on. But it wasn't easy concentrating. He thought about Peggy naked and walking, and then he thought about going to get her and carrying her back to bed. Or maybe he should wake Sam and tell him to get set for a brand new home, a place with lots of space and on a street that wasn't so damned noisy at night.

The more Hal Cooper thought about moving, the more he understood it was the perfect time. Sam would be starting school in earnest, so why not one of the better ones? As high as tuitions were these days, they could still probably afford that, too, right along with the new apartment. This was something else he'd have to talk to Peggy about—the right set-up for Sam, a first-rate private school.

The hell with the releases!

He got up and brushed his teeth and fingered cold water back through his curly, straw-colored hair. On his way to the kitchen he stopped and stood in the doorway of his son's room, his eyes measuring off the floor space almost gleefully, as if now, for the first time, its poverty couldn't threaten him or make him feel ashamed.

Damn it, the boy had no room to play! Anybody could see that. Of course they had to move. Why hadn't they thought of it the instant they'd heard about their promotions? God, it felt good to finally have some money.

As usual, the light summer blanket and the top sheet lay twisted on Sam's floor. His small, tanned body, sprawling in acrobatic slumber, was somehow draped more off than on the bed. Hal looked, and realized it was miraculous how a child could actually sleep in a position like that and what a lousy shame the miracle was ever outgrown. Then he tiptoed into his son's tiny room. For a time Hal Cooper stood listening to his son's sweet breathing, and then he leaned down and pressed his lips to the boy's long, silky hair.

***

The kitchen was ridiculously small—even by New York standards. But Peggy Cooper didn't seem to mind. She was more inclined to say what an advantage it was to have a layout that was so terrifically compact. After all, didn't it cut down on the steps you had to take to get a meal on the table and cleaned up again? Secretly, though, Peggy would have loved something spacious, a grand sort of country-style kitchen. What she wanted most was a kitchen with a window in it. Yet it wasn't in Peggy's nature to feel sorry for herself.

She was standing at the sink when Hal came from Sam's room, with her soft belly pushed up against the small patch of Formica counter and her short, shiny hair looking as if it had just been freshly arranged. There was a mixing bowl on the counter before her, and in her hand she still held the dripping shell of the egg she had cracked into the bowl minutes ago.

"Pancakes? Waffles? A little souffle?" Hal teased.

Peggy Cooper didn't answer at first, which wasn't like her at all. It was then that Hal saw that his wife seemed riveted by something that lay on the counter next to the bowl of unstirred batter.

He leaned his tall body against the doorjamb and smiled in a rascally sort of way.

"Mrs. Cooper? Hello, hello. It's Mr. Cooper over here. At least it was when I brushed my teeth."

Still Peggy did not answer. Her face was turned in profile, and it looked to him as if she gazed upon something that had struck her dumb.

"Honey? Pegs? You okay, baby?"

What the hell was she looking at?

"Hey, honey," Hal said again, more insistently, as he pushed away from the doorjamb and took the two short steps needed to put him next to her. He stood behind her so that he could peer over her shoulder.

Then he saw what she was looking at.

It was a drawing, one of Sam's, black ink on a white sheet from Sam's big Jumbo pad.

What Hal Cooper saw was a huge truck standing at the curb, four husky men frowning as they struggled with their burdens. They were loading the truck with furniture.

"Hey, that's great," Hal said, not understanding yet. But then he saw what Peggy saw—the big bentwood rocking-chair that stood in their bedroom and that Hal's dad had given them when they'd first set up housekeeping. It was an extraordinary rendering—the men, the van, the furniture. But it was the bentwood rocker, so perfect in every detail, that clinched it.

These were their own things, and a moving van had come to take them away.

CHAPTER TWO

Miss Goldenson was summering in Vermont, but Peggy decided the call would be worth it. After all, the woman was so terribly fond of Sam. Besides, she was a professional in these matters, and could be counted on to give reliable advice.

"Mrs. Cooper, I'd be more than happy to talk to you about schools for Sam, but I thought you'd decided to send him to the public school in your neighborhood."

Peggy hesitated. It seemed gauche to just blurt out that the reason she'd kept aloof from the insane Manhattan private school scramble that sometimes began when the city's young citizens were no older than three years of age had always had to do with money—and that now that she and Hal were making it she passionately wanted the "right" school for her child, and would do anything she could to get it.

She equivocated. "Well, Miss Goldenson," she began, clearing her throat, "my husband and I have given the whole matter a great deal of thought, and we've decided that Sam's education really has to be a top priority for us. I'm afraid no public school in the city would fill the bill, and as long as we've decided to go private, we may as well aim for the best."

"I couldn't agree with you more," the teacher replied, sounding as if she meant it. "Sam is a very special boy—genuinely gifted and talented—and I think a good prep school is exactly where he'll get the challenges and the stimulation he needs.

"But of course you realize," she continued, "that you'll have to apply him to several schools this September for a place the following year. It's harder to get into these private schools than it is to get in to college."

Of course Peggy knew all about that. Those of her friends who'd applied to private schools had carried on like crazy women all winter—waiting for the acceptances or rejections on which they seemed to feel their children's entire future hinged.

Which was why the conversation she'd had with someone in the admissions office at St. Martin's—one of the city's most exclusive schools—earlier in the day had seemed both so miraculous and so odd to her.

"Well," she said to Miss Goldenson in a voice both puzzled and elated, as the static crackled along the wire between Manhattan and Vermont, "I was fully prepared to go that route—send him to first grade in a public school while I waited for news about second grade. But I called St. Martin's this morning, and they said very definitely they wanted to interview him for this fall—even though he hasn't been tested or anything."

"But that's not possible," the astonished woman exclaimed. My God, it would be like getting into Harvard without taking the SAT's! "Are you sure, Mrs. Cooper?"

"Oh yes. Believe me, I'm just as amazed as you are. All the other schools I called told me the situation was hopeless for this coming year—they wouldn't even accept an application. And here we are with an interview at St. Martin's in a few days. St. Martin's! The best prep school in the city!" Despite herself, Peggy could not keep the note of jubilant yearning from her voice.

Long after the

y'd hung up, Miss Goldenson sat mulling over this conversation in the airless heat of the Vermont afternoon. What Peggy Cooper had told her was on the face of things absolutely incredible. Not that she would necessarily have chosen St. Martin's for Sam Cooper—it seemed a rather overly structured and stuffy place for such a creative little boy. But still, it was first-rate—there were parents all over the city who would have killed to get their kids in. Chiding herself for being so cynical, she couldn't help but wonder: Who had gotten to whom to arrange this unprecedented interview? Somebody'd been bought, she'd no doubt, but for the life of her, she couldn't think who.

***

For all her confidence in Sam, Peggy was nervous as hell about the upcoming interview. How do you interview a boy who's not even seven years old? Did they ask tough questions? Did they try to find out if you were the right sort of people or something? Did they have some tricky way of pinning you down, discovering that your parents went to state colleges and that your grandparents buttered the whole roll before taking the first bite?

Peggy checked with the older hands at Bloomingdale's—with some of the buyers whose business it was to stay up to date with the Manhattan social world. Had they heard of St. Martin's? Was it really all that grand? They all gave her the same report—a glowing one, a statement that was all the more convincing for the expressions that came over their faces.

The Boy Who Could Draw Tomorrow

The Boy Who Could Draw Tomorrow